FUTURESCAPE SUMMIT vol.1 第2部|ホストプレゼンテーション・ディスカッション

FUTURESCAPE SUMMIT Vol.1

【Part2|Host Presentations & Discussion】

2020年10月10日、公共空間を創造的に活用する世界諸都市と連携し、互いの経験と知見を交換し合うことを目的としたオンラインシンポジウム「フューチャー・スケープ サミット vol.1」を開催しました。

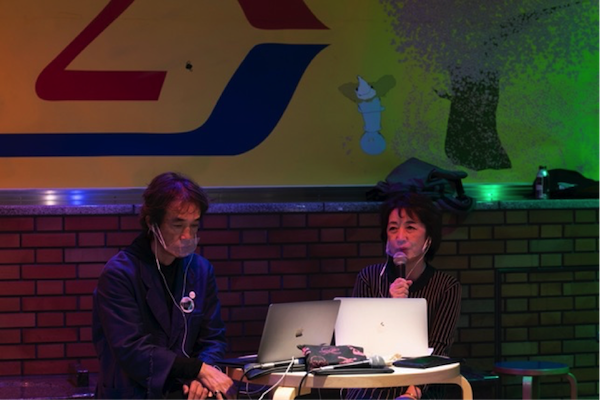

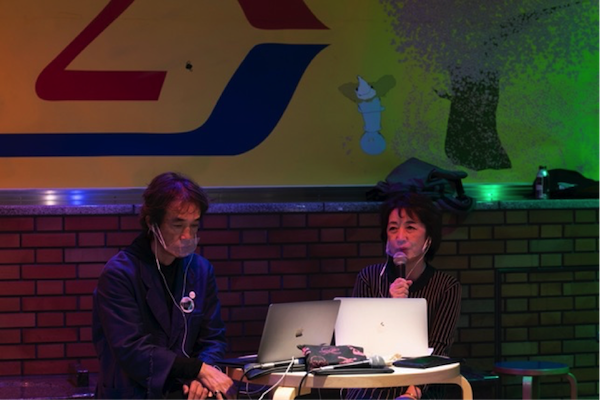

第二部では、横浜市文化観光局文化芸術創造都市推進部長の権藤由紀子、象の鼻テラスアートディレクターの岡田勉、アーティストの高橋匡太氏によるプレゼンテーションを実施。ゲストとのクロストークを行い、サミットを締めくくりました。

登壇者:権藤由紀子/横浜市文化観光局文化芸術創造都市推進部長

横浜市は、376万人という人口を擁する日本で最大の自治体です。161年前の1859年に、200年以上続いていた鎖国をやめ、外国に対して港を開いた最初の土地になります。それまでは100戸足らずの村でしたが、それから新しい文化や技術・人材が横浜に集まり、日本の近代化を牽引してきました。

第二次世界大戦で壊滅的な被害を受け、そこから復興を遂げる際に、かなり初期の段階から都市デザインという考え方を都市づくりに取り入れています。日本の近代化を支えてきた街並みをきちんと守り、魅力的な都市空間を作るということを大切にしながらまちづくりを進めてきました。

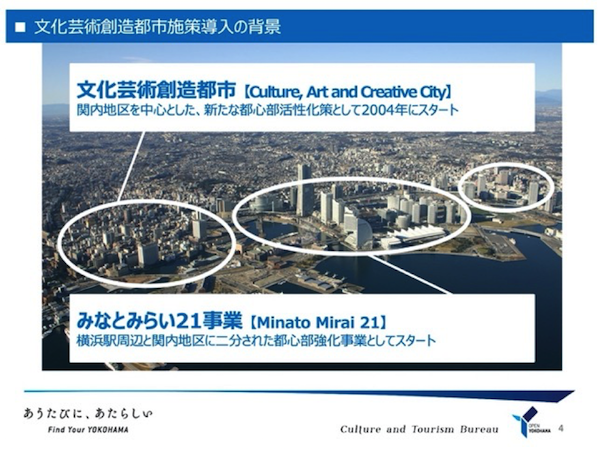

ただ、東京に非常に近接しており、高度経済成長で東京がどんどん発展していくなかで、横浜は東京に働きに行き、寝に帰ってくる「ベッドタウン化」が加速しました。これだけの大都市でありながら、昼夜間人口比率は9割を切るといったことが課題になり、20世紀の後半、都心部を強化しなければいけないということで、「みなとみらい21」という都心部強化事業をスタートさせました。構想が1965年、着工が1983年ですので、もう40年近い事業になります。

ただ、21世紀になり、業務中心の都心部づくりだけではうまくいかないということで、象の鼻テラスのある関内地区を中心とした次なる都心部活性化策として、「クリエイティブシティ・ヨコハマ」を2004年にスタートしています。その背景としては、歴史的建造物の減少、オフィスの空室率上昇、社会経済構造の変化があります。文化芸術の振興、創造産業の振興に向けて、クリエイティブな人材を横浜に呼び込むということを進めました。同時に、都市デザインを取り入れて作ってきた公共空間を活かし、より横浜らしい魅力的な都心形成の整備もやっていこうという、ソフトとハードの双方を組み合わせた施策としてやってきたところが、横浜の特徴だと思っています。

そのリーディングプロジェクトの一つが、既存の施設や歴史的な建物、空きオフィス、公共空間などを活用して、アーティスト・クリエイターが滞在制作・発表していく創造界隈の形成です。こういった拠点を複数、横浜市からNPO法人や民間の皆様に運営をお願いしています。関内外地区に集まったアーティスト・クリエイターが自分たちの仕事場・活動を見てもらう「関内外OPEN!」や、「スマートイルミネーション横浜」といった公共空間を活用したプロジェクトも行ってきました。

横浜が都心部強化をしていく中で、東京一極集中という状態がずっと大きな課題としてありましたが、今日のテーマであるポストコロナにおいては、人々が働いて暮らし交流し、多様な経験ができる場の価値が高まってくると思いますので、これまでの取組をさらに進化させていきたいと考えております。

登壇者:岡田勉/象の鼻テラスアートディレクター

私は東京のワコールアートセンターという民間企業が営んでいるアートセンターでキュレーターをしています。そこで培ったノウハウをたずさえて、2009年から象の鼻テラスの運営を担ってきています。なぜ「象の鼻」かというと、象の鼻のように湾曲している港の形にちなんでいるからです。港湾緑地という港にある公共空間の真っ只中にあるので、周辺の公園を使った取り組みが多く、我々のここでの活動の一つのミッションにもなっています。

コロナ禍で象の鼻テラスが2カ月ほど閉館した際には、ただ閉めておくわけにもいかないと、医療従事者の方々をはじめ、新型コロナウイルス感染拡大のなか働いている方々への感謝と敬意、そして応援を込めて「ブルーライトアップ」を行いました。

今回のテーマである、公共空間をより楽しもうという姿勢に至った動機の一つの事業についてこれからご紹介します。「スマートイルミネーション横浜」は、横浜は東京に隣接しているという土地柄、観光客が夜になると東京に帰ってしまうという悩みを持っていたので、それを解消するために夜間観光を促進しようと構想しました。2011年にスタートした事業ですが、ご承知の通り東日本大震災が起きたことで、パラダイムシフトが起きました。本当に根底から我々の暮らしについて考え直さないといけないという事態が生じ、それを受けて、スマートという言葉を付け、環境技術や省エネ技術とアーティストの創造性をかけ合わせた世界に類を見ないイルミネーション事業を立ち上げ、昨年まで取り組んでいました。

国連を中心としてSDGsに対する提言がなされ、横浜市でもSDGsデザインセンターができるなど熱心な取り組みが始まったことを受けて、スマートイルミネーション横浜は一旦終了しさらに発展させた事業にしていこうということになりました。そこで構想したのが、「フューチャースケープ・プロジェクト」です。

これは昨年象の鼻が10周年を迎えたこともあって構想したものですが、アーティストと市民の垣根を取り払い、公共空間を楽しむ欲求をいかに皆さんがお持ちかを推し量るために行った公募形式の事業でした。象の鼻パークがさらに居心地よい空間になるような未来の風景を想像する100のアイデアが寄せられ、寄せられたアイデアはとにかく全部実現しようということで100個のプログラムを実施しました。ほんの一部をご紹介します。

パフォーマンスを象の鼻パークで行う人たちや演奏会を行う人たち、障害を持つ方たちの車椅子のファッションショーなどたくさんのことが起きました。今回はこういったこれまでの取り組みを背景にしながら新しいスマートイルミネーション、新しいフューチャースケープ・プロジェクトを作ろうということで、すべての人の創造性がいきる公共空間、アートのためのということだけではなく、地球市民全体のために響くようなアートプロジェクトたりえたいという望みを持っています。

こうした構想を昨年来してきましたが、新型コロナウイルスの感染拡大により、スマートイルミネーションを構想したときと同様で、我々は困難に立ち向かっています。でも、それを乗り越えるのが使命のようなものだと思っており、常にアーティストたちと考えているわけですね。

この「たばこ」と書かれた看板を、アーティストの子どもたちが見たときに「たばゼット」と読んだそうで、子どもによる子どものための”たばゼットスタンド”、たばこスタンドとして駄菓子を販売するお店を実際に運営しているのですが、それを今回アートワークとして展示しています。日本には昔こういう看板を掲げたキオスクがたくさんあったので、それを再現しているわけですね。今日も実際に、インターネットでつながった店長を務める子どもたちが店番を行い、駄菓子を売っています。

Photo : Hajime Kato

日本には”スナック”というママがいてお客さんとカラオケをするような独特なバーのスタイルがありますが、コロナ禍でどうやって楽しむかということを考え、手話でスナックを営もうということをやりました。「ブルー・ライト・ヨコハマ」という横浜で最も有名な歌謡曲を、手話でカラオケしました。

インターネットを介した、オンラインとリアル空間を重ね合わせるようなこともやりました。たとえばこれは東京大学の筧康明先生が率いるプロジェクトで、スマホに息を吹きかけると象の鼻パークに設置されたシャボン玉機からシャボン玉が出るものです。

Photo:Hajime Kato

また、今回はWWFにもご参加いただき、このまま環境が悪化したときに日本の姿がどうなるかというプレゼンテーションもしていただきました。まだほんとに解答はありませんけども、こういう状況だからこそできることを美しく楽しく、アーティストとともに作っていけたらということで活動しています。

登壇者:髙橋匡太/アーティスト

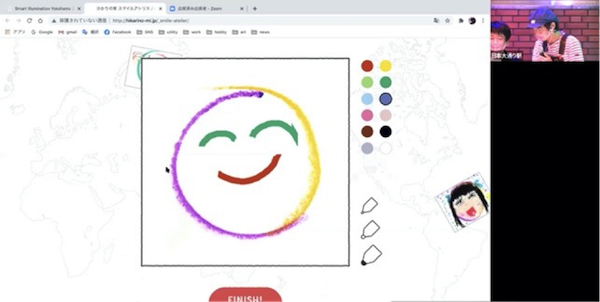

私からは、コロナ禍で実施したリモートワークショップ、「ひかりの実 スマイルアトリエ」についてお話をさせていただきます。

「ひかりの実」は、果実を育てるときに使われる果実袋に参加者が笑顔を描き込み、LEDライトを入れて樹に取り付けて、色とりどりの夜景をつくるという参加型のアートプロジェクトです。

Photo : Hideo Mori

「ひかりの実」を考案したのは2011年、東日本大震災の直後でした。被災地の住民たちが、電気などインフラが壊滅状態にあった状況でも子どもたちにイルミネーションを届けたいという思いを持っており、それに共感して発案しました。横浜の子どもたちと陸前高田の子どもたちが笑顔を交換するというプロジェクトで、同年末には被災地の陸前高田で子どもたちと一緒に「ひかりの実」をつくり、横浜の山下公園の樹に展示をしました。横浜で生まれた「ひかりの実」は全国に広がり、これまでの10年間で延べ10万人以上の笑顔が実りました。

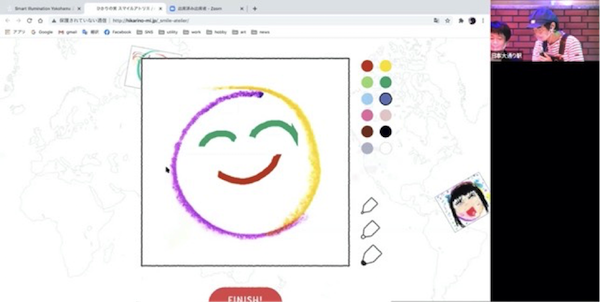

「ひかりの実」は、ワークショップを通じて笑顔について考えて、誰かの笑顔を描く、そんな制作の課程のコミュニケーションを大切にしています。しかし、コロナ禍でそうしたワークショップの場を持つことが非常に困難になってしまい、何か方法はないかと考えて、ウェブサイト上に世界中の誰もが参加できる「スマイルアトリエ」を作りました。このスマイルアトリエには、リアルで行われるワークショップの楽しさを可能な限り盛り込みました。

(実際にウェブサイト上で笑顔を描き込み操作をしながら)ここで描かれた笑顔は、フィニッシュボタンを押すと私のところに届きます。実際に世界中から投稿された笑顔のドローイングをUVプリンターで果実袋に印刷し、象の鼻パークの樹に展示しました。

先日は、香港の子どもたちと日本の子どもたちが同時に中継をつなぎながら楽しくワークショップを行いました。この経験は僕にとって新たな可能性を感じる、とても貴重な体験でした。この一枚のスクリーンショットが全てを物語ってくれています。完成した時の嬉しさ、同じ楽しい時間を過ごした喜びに溢れていて、遠く離れた香港の子どもたちと、何か気持ちを通わすことができた瞬間だと思っています。香港の子どもたちには、完成した展示風景や自分の作った「ひかりの実」の写真をお送りしました。きっと「遠く日本で自分のひかりの実が展示されたんだ」と、想像力の翼を大きく広げてくれていることと思います。それこそがアートの持つ一つの力だと、僕も勇気をもらいました。

ディスカッション

大田佳栄:

今世界ではこの新型コロナウイルスとの共存だけではなく、SDGsの達成なども大きな目標となっております。私たちはこうした社会課題に対してアートが何か力になることがあり得るのではないかと思い、特に公共空間の活用をテーマとした社会実験に取り組もうとしています。特にアーティストの自由な発想、振る舞いが市民を刺激し公共のあり方や公共空間の活用の仕方を拡張するのではないかという仮設をもってこのプロジェクトに取り組んでいます。皆様は、こうした社会課題の解決についてアートはどのように作用する、または作用する可能性があるとお考えでしょうか。

ロー・ヤンヤン:

このコロナ禍でいろいろな制限がありますが、異なるやり方、何らかの形でアーティスティックなやり方を楽しむことができると思います。いろいろな新しい考え方が出てきていますので、やはり全体として、アーティストの芸術的な観点から物事を発展させることを促進していかなければなりません。人々が社会の一員であるということを感じることが重要です。私たちはこのパンデミックの間、パブリックアートのマップをオンラインで作成したり、オンラインワークショップを行ったり、キュレーターやアーティストによるARの展示ツアーをスマホのアプリで提供したりといったデジタル戦略をとってきました。より広く一般の方にリーチし、それぞれの感性で私たちのプロジェクトを解釈していただきたいと思っています。

アッベ・ロビンソン:

今の状況というのは非常に興味深い課題をアーティストに投げかけていると思います。アーティストというのは常に人々の経験にもとづいて、それを制作に反映しているので、今の現状もいろいろなチャンスにつながると思います。そうすると人々のエンゲージメントの仕方、特に公共の関わり方というのも変わってくると思います。フェスティバルディレクターとして管理の仕方を変えていく必要もあります。公共との関わり方も違ってくるかと思います。

私たちのフェスティバルは通常は街の中心部で開催しますが、今年は舞台を空に持っていくことで、新しいオーディエンスを獲得することができると考えています。街なかへ移動しなくても、自宅の庭から、自分たちの地元エリアから、見上げるだけで鑑賞できるからです。このコロナ禍の状況に対応し変化することで、結果的にこれまでとは違うコミュニティ・属性の人々を巻き込むことになることはとても楽しみにしています。

ルーシー・ダスゲート:

アートというのは、ニューノーマルに戻るための足がかりになるのではないかと思います。社会を元のようにつなぎ合わせる手法として、行政が積極的に取り入れるべきものだと思います。地元にしても国際的なものにしても、人とのつながり、コミュニティの一員であるという実感を持つことは人々にとってとても大切なことです。引き続き国際的な結びつきを深めつつ、地元のコミュニティも大切にしていきたいと思っています。

守屋慎一郎:

非常に素晴らしい意見が出ていると思いますが、岡田さんに、フューチャースケープ・プロジェクトに取り組んでみての手応えや、アートはこういう役割を果たし得るのではないかということなどありましたらお話しいただきたいと思います。

岡田勉:

アーティストの創造的で自由な眼差しを、市民生活やまちづくりに生かしていかなければもったいないなということを改めて思いました。今回の皆さんのお話を聞いていて、アートと市民と公共空間の距離感の持ち方に少し差があるようなので、こうした議論をぜひ継続し深めていけたらより豊かな公共空間やまちが作っていけるのではないかと希望を持ちました。

守屋:

髙橋匡太さんは、コロナ禍があったからこそ、可能性に気づけたというところはありますか。

髙橋匡太:

子どもたちの笑顔や、一緒につくるということの喜びは変わらないんだなということを改めて実感しています。非常に閉塞感がある中で、インターネットというプラットフォームを使って誰かとつながりたいという思いがより強くなり、こういうきっかけでもなければひかりの実のプロジェクトが一気に世界の子どもたちとつながるというところまでいかなかったと思います。ある意味逆境を次のステップへのチャンスに変えていけるのではないかと、僕自身はすごくポジティブになっています。

守屋:

今日の議論を聞いていていくつも印象に残るキーワードがありましたが、アーティストの自由さと、その一方で持っている自分の表現に対する責任ですかね、そういったものがコロナ禍の時代にひょっとしたら何か新しい可能性を開いていくのではないか、コロナ禍後の社会全体の設計に非常にポジティブな影響を与えていく可能性があるのではないかということを感じたサミットでした。

権藤由紀子:

皆様ありがとうございました。こういった厳しい状況だからこそ、それをチャンスに、ニューノーマルにチャレンジしていきたいという勇気をもらえた時間でした。こういう時だからこそ多様性を認め合い、力を合わせ、社会の一員であるという実感を皆が持てるような取組が必要です。公共をつくっていく働きかけの中でどうクリエイティビティを発揮していくのか、自由と責任を持ってどんどんチャレンジしていく、そのための環境を整えていきたいと決意を新たにしました。これを機会に皆様と引き続きつながっていきたいと思いますのでよろしくお願い致します。本当に今日はありがとうございました。

On October 10, 2020, in partnership with cities worldwide that creatively use public space, Zou-no-Hana Terrace held Futurescape Summit Vol. 1 with the aim of exchanging experiences and insights.

The second part of the summit featured presentations from three speakers: Yukiko Gondo, Executive Director of the Culture, Art and Creative City Promotion Department, Culture and Tourism Bureau, City of Yokohama; Tsutomu Okada, Art Director of Zou-no-Hana Terrace; and the artist Kyota Takahashi. This was followed by a crosstalk with the guests from the first part to bring the summit to a close.

Speaker: Yukiko Gondo (Executive Director of the Culture, Art and Creative City Promotion Department, Culture and Tourism Bureau, City of Yokohama)

With 3.76 million residents, Yokohama is the largest municipality in Japan in terms of population. Its roots go back 161 years to 1859, when it was the first place to open up to foreign trade and end the policy of isolation that had continued in Japan for over two centuries. At the time, it was no more than a village of a hundred households, but new culture, technology, and human resources subsequently gathered in Yokohama, and it would become a leading force in the modernization of Japan.

During World War II, the city suffered devasting damage and as it underwent recovery, it incorporated city planning ideas from quite an early stage. The city set out to redesign itself in a way that preserved its identity as a foundational place in the modernization of Japan while also creating an attractive urban space.

But as Tokyo increasingly developed during the period of rapid economic growth, the very closely located Yokohama found itself relegated to a commuter town: a place from where people left in the mornings to go to Tokyo to work and then came back to at night. Despite being a very large city, its nighttime population was far higher than its daytime one, an issue that led to a desire in the second half of the twentieth century to improve the city center, resulting in the launch of the Minato Mirai 21 initiative. The plan was proposed in 1965 and construction began in 1983, meaning the development is now ongoing for around forty years.

Entering the twenty-first century, simply developing a central business district was not enough, and a new initiative was launched in 2004—Creative City Yokohama—as a way to revitalize the Kannai district, where Zou-no-Hana Terrace is located. The context for this was the declining number of historical buildings, the rising office vacancy rate, and changes to socioeconomic structures. The city made efforts to entice creative people to Yokohama in order to promote culture and the arts, and the creative industries. Pursuing policies that combine both soft and hard approaches—simultaneously harnessing public space that incorporates urban design and reshaping a city center that better demonstrates the distinct appeal of Yokohama—seems characteristic of the way that Yokohama does things.

One of the lead projects is making use of existing facilities, historical buildings, vacant offices, and public spaces to form creative districts where artists and creative talent can stay and present their work. These bases or hubs are managed by nonprofits or the private sector on behalf of the City of Yokohama. Some of the projects we have done using public space include “Kannaigai Open!,” in which artists and creatives in the Kannai and Kangai areas let members of the public into their workplaces, and Smart Illumination Yokohama.

While Yokohama continues to strengthen its city center, the excessive concentration of people in Tokyo remains a major problem. But in terms of what comes after the coronavirus pandemic, which is something we are discussing today, I think that we will see places where people can live, work, and interact, and have different kinds of experiences increasingly gain in value, and so I hope to further develop the efforts we have made until now.

Speaker: Tsutomu Okada (Art Director, Zou-no-Hana Terrace)

I am a curator at Wacoal Art Center, which is a privately run institution in Tokyo. With the know-how we built up there, we have been running Zou-no-Hana Terrace since 2009. The name, which literally means “elephant nose,” derives from the shape of the bay that apparently resembles an elephant’s nose. It is located right in the middle of the green public space in the port area, so many of projects we do make use of the surrounding park, which is one of our missions.

Due to the coronavirus pandemic, Zou-no-Hana Terrace was shut for two months. During that time, the site was lit up in blue to express our gratitude, respect, and support for all the people striving to combat the virus, not least medical workers.

I would like to introduce an initiative that led to our desire to make public space more fun, which is our theme this time. Smart Illumination Yokohama was envisioned as an event to promote nighttime tourism in order to eliminate the problem that because it is a neighboring city to Tokyo, visitors to Yokohama tend to go back to the capital at night. It was launched in 2011, which, as you know, was the year the Great East Japan Earthquake happened and ushered in a paradigm shift in Japan. We found ourselves in a situation whereby we had to really rethink our lives from the bottom up and so, taking that on board, we launched this globally unique illuminations event that combined artistic creativity with environmentally friendly and energy-saving technology, all brought together under the umbrella of “smart.” The event was held until last year.

The City of Yokohama has also engaged enthusiastically with the sustainable development goals proposed by the United Nations, such as establishing the Yokohama SDGs Design Center, and it was also decided to stop Smart Illumination Yokohama for now and develop it further. The plan that emerged from this was the Futurescape Project.

This was envisioned for the tenth anniversary of the Zou-no-Hana last year, when we held an open-call project in order to tear down the barriers that separate artists and audiences, and surmise the extent to which people want to enjoy public space. We collected a hundred ideas that imagined the future landscape in which Zou-no-Hana Park becomes an even more comfortable space, and then organized a hundred programs attempting to make these ideas a reality. I will introduce a few of these.

Lots of things took place, from a performance in the park to a musical recital and a fashion show of wheelchairs for the disabled. We next wanted to create a new smart illuminations event and new Futurescape Project against a backdrop of these initiatives we have done until now, hoping to make public space that allows everyone to flex their creativity, to be a project that not only provides a platform for art or but also resonates with all global citizens.

This idea was something that we had last year, but the coronavirus pandemic has since meant we once again face serious social dilemmas like we did when we conceived the Smart Illumination event. But I think it is our mission to overcome that and we are always thinking about this with artists.

For one program for this year’s Futurescape Project, children are the artists. The kids who started it would apparently misread “tobacco” on a sign as “taba-zed.” This inspired an artwork: a candy stand called Taba-Z, made by kids, for kids. In Japan, there used to be lots of these kinds of kiosks and this is an attempt to recreate one. For the Futurescape Project, the children are taking turns to run the shop and sell sweets, in person or remotely via the internet.

Photo : Hajime Kato

In Japan, there is a unique kind of bar called a “snack,” with a female proprietor known as the “mama” and where customers sing karaoke. We were wondering about how people can have fun during the pandemic and so we decided to open a snack bar where you use sign language. At the bar, people sing renditions of “Blue Light Yokohama,” the most famous song about Yokohama, in sign language.

We also harnessed the internet to combine online and offline spaces. For example, this is a project led by Yasuaki Kakehi of the University of Tokyo, where blowing on your smartphone results in bubbles coming out of a machine set up in Zou-no-Hana Park.

Photo:Hajime Kato

The World Wide Fund for Nature also took part in this year’s Futurescape Project, where it gave a presentation about what Japan will look like if the environment continues deteriorating like it is now. We still don’t have the answers, but the circumstances in which we find ourselves at present mean we are working with artists to do what we can in ways that are beautiful and fun.

Speaker: Kyota Takahashi (artist)

I will talk to you about “Hikari no Mi Smile Atelier,” a remote workshop that was held during the coronavirus pandemic.

“Shining Smile Fruit” is a participatory art project in which people draw smiling faces onto the plastic protective bags used to grow fruit, into which are placed LED lights and then hung from trees to create a colorful nightscape.

I came up with the “Shining Smile Fruit” project immediately after the Great East Japan Earthquake. I was inspired by how the residents in the disaster areas wanted children to experience the joy of illuminations even though they were living in conditions where electricity and such basic infrastructures were no longer available. As a project for children in Yokohama to exchange smiling faces with the children in Rikuzentakata, we made the “Shining Smile Fruit” pieces together with local kids in Rikuzentakata at the end of 2011, and these were then exhibited on trees in Yamashita Park in Yokohama. Though started in Yokohama, the “Shining Smile Fruit” project has now spread nationwide and over ten years cultivated smiles on the faces of more than 100,000 people.

“Shining Smile Fruit” prizes the communication that takes place over the course of workshops where people think about smiling faces and then draw one. But the coronavirus pandemic has made it very hard to hold workshops in person, so we wondered if there was an alternative approach we could take, and so we came up with “Smile Atelier,” which takes place online and allows anyone around the world to participate. While held remotely, we incorporated the fun of an in-person workshop as much as possible.

[Takahashi demonstrates drawing a smiling face on the website.] The smiling faces created here are sent to me when you press the final button. These drawings of smiling faces posted from anywhere across the world were printed onto fruit bags by a UV printer and then exhibited on trees in Zou-no-Hana Park.

The other day, we held a live online workshop with children in Hong Kong and Japan, each in their respective locations. This was a very important experience for me where I could sense new potential. This single screenshot tells the whole story. Overflowing with the joy they felt when they completed their work as well as the happiness from spending a fun time together, this was a moment when I could pass on feelings to children in faraway Hong Kong.

To the kids in Hong Kong, I sent photos of the finished exhibition and the “Shining Smile Fruit” piece they had each made. I think that they expanded the scope of their imaginations, knowing that their work is exhibited faraway in Japan. I was encouraged by this: it is a power unique to art.

ーー

Discussion

Yoshie Ota: Though we are searching for ways to live with the coronavirus, achieving the SDGs is also a major goal for people around the world today. We wondered if art is able to do something about these social challenges and have attempted to engage in social experiments exploring, in particular, the use of public space. For this project, we have operated under the assumption that the free imagination and behavior of artists can inspire members of the public, and could expand approaches the public sphere and the use of public space. What does everyone think about the effects art has or its potential effects in regard to these social issues?

Lo Yan-yan: The pandemic has led to various restrictions, but it also means we can try different approaches or artistic ways of doing things. Lots of new ideas are emerging and we must now continue to develop things from artistic perspectives. It is important for people to feel that they are members of society. During the pandemic, we engaged with digital strategies, creating public art maps online, holding workshops remotely, and offering a phone app with an augmented reality experience as well as exhibition tours hosted by curators and artists. By doing this, we hope to reach a broader audience and to encourage people to interpret our projects in their own ways.

Abbe Robinson: I think that all these kinds of situations present an interesting challenge for artists. Art always reflects human experience, so I think the current situation is going to create a lot of opportunities to explore how it’s affected us, both individually and collectively. Some of the projects that will come out of that will be really fascinating. It will change the way in which people engage with the public realm. We have a lot to explore in the way that we manage that as festival directors.

Our festival normally takes place very much in the confines of the city center, but taking our project up into the sky this year means we will potentially engage with a new audience. They will be able to watch the festival just by standing in their own gardens in their own areas of the city and looking up, without having to travel into the city center. By adapting and changing to the circumstances of the pandemic, we’re actually going to engage with different communities and demographics, which is quite exciting.

Lucy Dusgate: I think art will be part of the gateway back to a new normality. I think it’ll be something that helps all of us and should be proactively seized and taken on board by authorities as a way of connecting societies back together. It is incredibly important for people to feel like they still have a sense of home, a sense of touch, a sense of being part of a community, whether that be a local one or an international one. We should keep trying to work together both internationally as well as locally for our communities in our neighborhoods.

Shinichiro Moriya: These are wonderful things to hear. Tsutomu Okada, could you please tell us about the response you saw to the Futurescape Project, and your opinion about the role of art in this regard?

Tsutomu Okada: It left me with a renewed feeling that it is such a waste if we don’t harness the creative, free perspectives of artists for people’s lifestyles or community development. Listening to what everyone has said today, there are some differences in terms of the sense of distance between art, citizens, and public space, so I have hope that by continuing to deepen these discussions, we can create public space and cities that are more enriching.

Moriya: Kyota Takahashi, did you come to realize any possibilities because of the coronavirus pandemic?

Kyota Takahashi: I gained a renewed sense that the joy of seeing the smiling faces of children and of making something together does not change. When life feels incredibly restricted, my desire to connect with others through online platforms is stronger and without this impetus, the “Fruits of Light” project would not have reached children globally so quickly. In a sense, we could transform adversity into an opportunity to take things to the next level, so the outcome for me personally was very positive.

Moriya: Listening to the discussion today, several keywords left an impression. This was a summit in which I felt that artistic freedom and, on the other hand, responsibility for self-expression might well open up new possibilities during the coronavirus pandemic, and have the potential to impact the layout of the post-coronavirus society as a whole in extremely positive ways.

Yukiko Gondo: Thank you, everyone. I was encouraged by how it is precisely these kinds of tough times when we should seize the opportunity to try out new things in the new normal. It is in just such times as these that we need to recognize diversity, join forces, and embark on efforts with a keen sense that we are all members of society. How can we flex creativity while working to shape the public sphere? I am newly resolved to set up environments for making endeavor after endeavor freely yet responsibly. I hope we can build on this opportunity by remaining in touch with one another in the future. Thank you very much for participating in our discussion today.